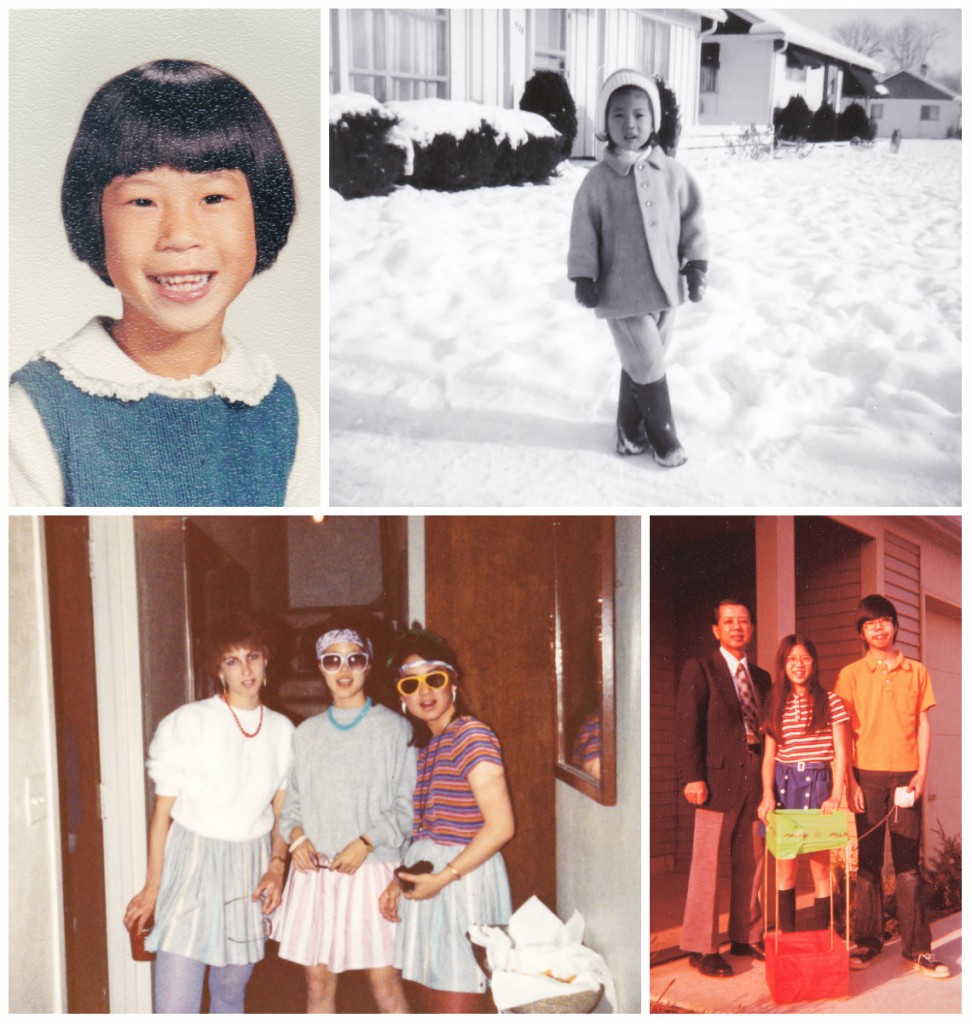

From the beginning, I stood out–in a not-so-good way. I grew up in the ’60s, in Fort Wayne, Indiana– a city of 250,000, where there were exactly three Asian families (and we were all related).

My family yearned to blend in, to be like everyone else. My father bought a small tract home in a neighborhood of young families. But we were obviously different. No other family on the block had a duck hanging from the carport ceiling, drying in the open air (part of our cooking process). Our evening meal was rice, and Chinese dishes with odd smelling vegetables that had no English name. My parents spoke to me in Cantonese. I replied in English.

Being different created problems.

Neighbors and classmates, staring, didn’t know what to make of me. Kids pulled at the corners of their eyes, mimicking the natural shape of my own. Walking home from kindergarten, a boy pushed me into a mud puddle. Some thought I was exotic. In first grade, a classmate said he wanted to kiss me after school. That terrified me.

I navigated two worlds as best I could.

I didn’t talk about the Chinese part of my life–like receiving red envelopes on New Year’s Day and watering bean sprouts in the garage–and no one asked. In high school, I chose activities that made me feel like I fit in. Marching band, tennis, an after-school job surveying customers about repairs on their phone lines.

There were signs of tension between my two worlds. My father wrote to my sister, who was married and living overseas : “Carol is sticking out like a sore thumb. She had the highest grade point average in her class.” American individualism meets Asian conformity.

*******

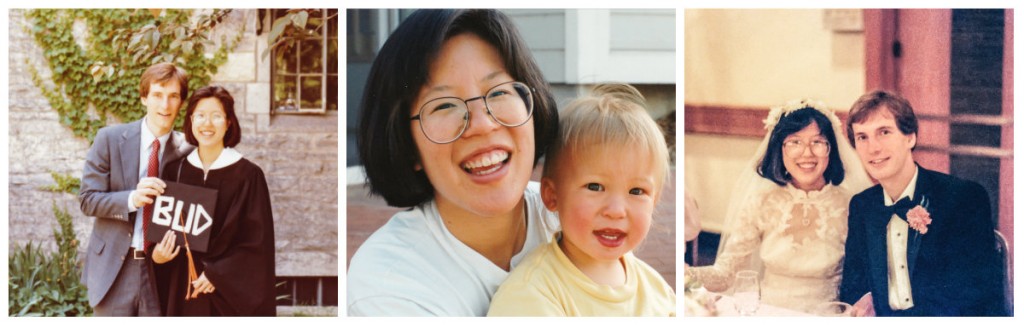

Entering college, it seemed like the world was adapting to who I was. There were smart, Asian students in my engineering classes. I met my college sweetheart, who later became my husband. I felt at home.

This feeling was short-lived. After graduating, I worked in a nuclear power plant, still under construction, 60 miles outside of Chicago. There were 3,000 male unionized workers on site. As one of a handful of women engineers, getting to my office in the middle of a plant was akin to walking through a lions’ den. I supervised technicians who were decades older. The topic of lunch time conversation ranged from last week’s bow hunting trip to memories of being on a Navy nuclear submarine.

This feeling was short-lived. After graduating, I worked in a nuclear power plant, still under construction, 60 miles outside of Chicago. There were 3,000 male unionized workers on site. As one of a handful of women engineers, getting to my office in the middle of a plant was akin to walking through a lions’ den. I supervised technicians who were decades older. The topic of lunch time conversation ranged from last week’s bow hunting trip to memories of being on a Navy nuclear submarine.

I was clearly an outsider.

The stress of not fitting in took its toll. Three years into my job, I left for grad school. After getting a master’s in engineering, I took R+D jobs where my colleagues were well-educated, analytical thinkers. Things worked...for a while.

There were reminders that I did not fit the mold. I worked in telecommunications, where it was common to see Asian immigrants who had come to the U.S. for grad school and stayed for engineering jobs. A colleague once told me: “Carol, when you open up your mouth at technical conferences, you surprise people.”

I asked Pete, a good ol’ boy from Virginia, what he meant. He explained that from looking at me, strangers assumed that English was a second language. My words—persuasive and glib--did not match the image.

At some point, life delivers a wake-up call to abandon what you know for something that is not yet formed.

Things shift, and “here” quickly dissolves. There is only a faint inkling that in the long run, you will be better off.

This is what happened in my 30s. I had two babies. Becoming a mother triggered me to examine my life. I entered therapy. Stress was slowly grinding my teeth down to an unnaturally smooth surface. The cognitive dissonance increased. I was an engineer, but technical work was no longer satisfying.

The path I was on did not match who I was, as a whole person.

I was ready to reinvent myself. To leave behind my parents’ image of success. But if I wasn’t an engineer, what was my place in the world?

Being competent was no longer enough. I wanted meaning. The way forward was to tap into my creativity and listen to my inner voice.

I followed my curiosity and learned by trial and error.

My interest in how to make teams work better—I was on a team of 25 software testers—evolved into a passion for organization development. I swapped technical systems for human systems. By reading journals and books, I learned the theory. By volunteering to help with team retreats, I found what worked.

My interest in how to make teams work better—I was on a team of 25 software testers—evolved into a passion for organization development. I swapped technical systems for human systems. By reading journals and books, I learned the theory. By volunteering to help with team retreats, I found what worked.

Over time, I saw myself differently. My work brought me alive.

No longer trying to fit in, I saw new opportunities.

I created a new position within the technical ranks, to stem an outflow of engineers. Colleagues, with decades of experience, left for other companies, ostensibly for higher pay. The book, First, Break All the Rules, changed my mind about why employees leave. The authors described factors impacting retention, none of which had to do with pay, and everything to do with how employees were being treated. Turnover was a solvable problem. I approached a fellow engineer who had moved into a recruiting role and said, “It’s doesn’t do any good to hire more people if you can’t retain them.” He agreed and got the funding for my new role of Retention Leader.

I was forging my path among 32,000 employees, intent on creating a workplace that valued heart as much as head.

*******

I stumbled upon the power of story to transform how we see and live our lives. I was asked to manage new hire onboarding. Instead of delivering dry slides, I invited VPs, technical gurus, and middle managers to tell stories of their careers. They showed the many paths that one’s career could take.

These monthly talks served as a corporate campfire. We sat in a circle, a dimly lit room illuminated by candles burning in the center. (How I never set off the fire alarm, I’ll never know.) After one talk, an engineer told me: “I was discouraged about my career. After hearing these stories, I have hope again.”

These monthly talks served as a corporate campfire. We sat in a circle, a dimly lit room illuminated by candles burning in the center. (How I never set off the fire alarm, I’ll never know.) After one talk, an engineer told me: “I was discouraged about my career. After hearing these stories, I have hope again.”

Speakers were impacted as well. Many were connecting the dots of their lives, making meaning of twists and turns in a long career. Executives talked about juggling business trips to share custody of children and getting bad performance reviews. Technical gurus recounted unconventional assignments. Managers shared wisdom gained from their biggest failures.

We spoke from the heart, and we were all better for it.

Finding kindred spirits—people who “got” what I was trying to do—helped to establish a new identity. I began to build my tribe. They ranged from a Muslim engineer who appreciated the designation of a meditation room for daily prayers, to managers who acknowledged their staff with hand-written thank you notes, to a woman at a national organization –Spirit At Work– who wanted to nominate me for an award.

I was out in front…and I was not alone.

This bliss did not last long. Less than a year later, the tech bubble burst. My company began shedding workers. Retention was no longer a concern. Once again, I was trying to find my place.

*******

In 2002, I was laid off. It was blessing in disguise--an opportunity to “live a bigger story”. Time to forge my own path, not just in a company, but in the world. I became an entrepreneur.

At last, there was no box to fit into. No two entrepreneurs are the same.

While my engineering mind figured out how to run a business, I was delighted to tap into my creative side. Blogging became a way to tell stories. In coaching school, I learned to trust my intuition. I discovered that I loved working with “boundary crossers”—people who walk in more than one world but fit wholly in no one world. (Think software developer by day and theatre director by night.) It was a relief to find others like me, whole brain thinkers using both intuitive right brain and logical left brain.

One of the greatest joys in life is to stand out and belong, at the same time. Fitting in is about sacrificing part of who you are to conform. Belonging is about being accepted for who you are.

As I became comfortable in my skin, my tribe grew. As I gained the confidence to "let my flag fly high", to be fully seen, kindred spirits gathered. People responded to authenticity and creativity, whether I wrote a funny article about buying toilets or poignant lessons learned from being laid off. My audience loved it when I held a virtual “Summer Solstice Party”, challenged them to fly 2,000 miles for dinner, and taught how to network naturally, using a cow metaphor.

As I became comfortable in my skin, my tribe grew. As I gained the confidence to "let my flag fly high", to be fully seen, kindred spirits gathered. People responded to authenticity and creativity, whether I wrote a funny article about buying toilets or poignant lessons learned from being laid off. My audience loved it when I held a virtual “Summer Solstice Party”, challenged them to fly 2,000 miles for dinner, and taught how to network naturally, using a cow metaphor.

Being different made me remarkable, rather than broken.

Genius comes from following your own path. As an engineer, my work was accurate and detailed, but without passion. As a coach and a writer, my tribe tells me I’m brilliant.

Looking back, three elements were necessary for forging my path: Self-Mastery, Story, and Tribe. Making meaning of your life—telling your story—comes only after you understand who you are and what gets in your way. Connecting with others—building your tribe—is easier once others know your story. When you have your tribe, fitting in becomes a moot point.

No longer defined by one world or another, but rather valued for all of who I am, I have traveled the journey of Career Integration. What I’ve done for myself is what I help others to do.